Matilda Empress Read online

Page 26

Then, with my two faithful servants, I ran six miles to Abingdon, through high drifts and muddy ditches, hardening myself against the yelps of werewolves: savage, cannibal creatures, once men until the fury came upon them. At Abingdon, we claimed horses and galloped astride, nine miles east to the isolation of Wallingford, FitzCount’s own castle.

†

FitzCount’s stronghold rejoices over our recovery; their sumptuous hospitality does not ebb. Still famished, we overstuff ourselves to nausea at every midday meal, then nap away the short afternoons.

The romantic imprudence of my loyal vassal annoys me. He is ever underfoot, and resists when I would shoo him away. “No one has the right to be indignant if I dedicate myself and my deeds to Your Majesty’s service, and acknowledge you as my foremost mistress. On the contrary, I am bound to be extolled and avoid all stigma of wantonness.”

But my heart is walled off, interred in an abyss of grief. Brian overflows with affection, but I cannot let him fill me up with his tenderness. I would leave my soul empty, colossal, titanic.

†

The beauty of FitzCount’s wife, Basilia, has been much exaggerated. With her cornflower hair and unlined face, she resembles a child, or a fairy. It bemuses me to see my knight hounded in turn by her unrequited infatuation. Her eyes, dark brown, very deep, dart after her husband as he dogs me, catering to my whims. As the days pass, she sours with the knowledge that he worships me with more than a political fervor. Contrary to his view of her prerogatives, she resents his ill-concealed desires and flaunted subservience to me.

Last evening, in the dusk of vespers, already retired to my guest quarters, I heard a sharp, hacking sound coming from the inner ward. Standing so that I could look out from the slit window in the wall, but not be seen to be spying, I watched a hooded Basilia hammering one rather large boulder against another, which lay embedded in a small depression on the ground. Holding my breath, I could make out the words of her spell: “I do not pound these stones together, but beat and smash the essence of him and her, whose names are etched upon them.” I exhaled, and saw that she picked up a spade, to cover the rocks with mud.

Once the darkness of compline had fallen, and Brian’s wife had evaporated back into the castle, Gerta ambled outside, accompanied by a Herculean soldier partial to her face and form. He had a battle-axe in the crook of his elbow. My maid simpered becomingly, presumably urging him to show off his purported strength. The warrior exhumed Basilia’s fragments and further buffeted them to pieces, before kissing Gerta’s hand. My maid picked up the shards and stuffed them in a leather satchel; her admirer slung it over his shoulder. Arm in arm they wandered off, so that she could reward his fortitude and his discretion.

Now these broken shreds of stone smolder among the embers of my fire. If anything is left of them, when we depart from this keep, I shall tumble what remains into the moat.

Does Basilia think that her pixie magic can sever the sworn bonds of fealty between a chivalrous knight and his lady?

†

My benighted cousin takes Oxford. Within hours of my departure, the garrison and the townsfolk surrendered to the pretender. Generously, my cousin pardons my guards and courtiers, permitting them to disperse. But the main routes, from London to Gloucester and from Southampton to the Midlands, are his. Despite my trick, our adversary retains the upper hand.

Gloucester, apprised of my flight, marched his forces to Wallingford. Reunited with my brother, I am primed to share the burden of the resistance. The earl’s praise for my daring exploit encourages my renewed sense of purpose.

Discovering the Plantagenet safe, grown tall and strong, I am glad beyond measure. Already, Blessed Mary rewards me for my sacrifice of the Count of Boulogne, and redirects me, toward my son and his future.

Tonight, at Brian’s board, we feasted on piglet, stuffed with compote of nuts, scrambled eggs, bread, dates, and spices.

Seated next to my heir, I fluttered over his face and form. “This evening, it is almost possible to be negligent of the misery and discord that swirls around us.”

Henry grinned exuberantly. “We are winning your war, Mother. Our armed campaigns are like waves, crashing repeatedly upon the helpless shore. The Lord’s hand is visible in every one of our triumphs.”

I considered the warmth in my belly. “My own escape is one of the Glorious Virgin’s proven miracles.”

The Plantagenet glowed, for I am no coward. “It is said to be so, by every minstrel in the land.” His red head dipped down, as he stuffed his mouth full of fruit and meat.

I grinned, as I used to. “I have hired notaries to record my daring and Our Lady’s wondrous support of me; they write it down in the annals of every church in Oxfordshire. Some of them embellish the historical account with details of their own invention. One claims that I adorned myself in Mary’s most holy shift, which she wore to give birth to Our Savior. Only this robe was unspotted enough, white enough, to blend in with the snow, and pure enough to safeguard me among impious traitors.”

The prince smiled, his lips red with juice. “The shift was smuggled out of Constantinople on the orders of Charlemagne! Your supposed tie to it will heighten our stateliness in times to come.”

FitzCount arose to oversee the changing of the watch upon the battlements.

Once he was out of earshot, Basilia’s opaque eyes pulsed. “Empress, your boy’s red hair quite strikes my fancy. It puts me in mind of His Majesty.”

I was careful to speak languidly. “We are cousins.”

Brian’s wife hissed.

I smelled her breath, acrid, like mustard. “Are you named for the evil basilisk, half fowl and half serpent?”

Basilia pursed her lips. “Very few disparage me without coming to regret it.”

Henry Plantagenet shook his amber head. “Hold your sniping tongue, woman.”

Whatever it takes, I shall depose the father and elevate the son. Hail Mary, Vindictive.

The Matter of

the Crown

Scroll Fifteen: 1143

Do not suddenly rise up from your cushioned seat, and discount this history of conceit and deception, supposing it merely the work of the devil. Even worthy men took up arms in iniquity, so that bustling villages once celebrated stood desolate, and noble castles, once mighty, fell into decay. The empress’s own tragedies hardened her to the miseries of her people. She frolicked in corruption, to ease her own burdens. Englishmen prayed in vain; in retribution for the sins of the ream, heaven withheld its mercy. Much was the wicked Matilda to blame.

†

Winter

My brother, my heir, and all my most important vassals reestablish my court at Bristol. Despite his youth, the Plantagenet’s presence facilitates the recruitment and retention of our partisans. Most are in good spirit, given the broad consensus that the true prince abides among us.

Adeliza sends me word; her letter flusters me, for its tone is less conciliatory toward me than I deserve, for all that she remains loyal to young Henry.

The king to come sets his foot on English soil, despite the hazards of a winter sailing and the swirling civil disruption. Neither could deter he whom I would honor as Jesus, son of Mary, he who will release his subjects from the evils of war. Your son rises; we must all unite to keep him clean of blood. In the time before, your anger oppressed the land, but now your zeal is righteous, for you are whole like the Virgin and Christ is God and man.

†

The winter settles itself down upon us. Hour after hour, we loiter in the great hall of the citadel, warming ourselves by the radiant hearth. When our conversation palls, we gloat over my boy’s marvelous arrival.

Today, I bored him with more such talk. I cuffed him on the arm. “I have confidence in you, in the wonder of you.”

Henry tossed his head with impatience. “The antlers of the stag would be miraculous, if they were not its natural crown.” The pretender’s son displayed Geoffrey’s fine mind.

I tested the

prince’s logic. “But what of this? The flesh of a corpse is eaten by worms, but reconstituted whole in paradise.”

“God can subvert the laws that order His creation.” Snagging an earwig from among the floor rushes, he tossed it into the fire, snickering when it sizzled.

FitzCount sat with us; he has always been fond of my heir. “What news of your two brothers, long unseen?”

“I have been at Angers with young William, now six. We are seen to by Denise, my father’s leman; we have been brought up with her twins, Hamelin and Marie, who are eleven. My brother Geoffrey, eight now, lives further south in Anjou, in Saumur.”

I sniffed at the mention of that slut, once so much my rival. “Tell me about the young lady. Does she still compose fanciful poetry?”

The Plantagenet flushed. Was it from the heat of the blaze? “Marie’s agitation at my departure was improper. She claimed that she could not exist without me, that I am her only joy.”

My jaw hinged open. “Then it is fitting that you were banished from her side.” I closed my mouth, remembering my first kisses.

Sir Brian coughed. “Denise should intervene, or counsel her daughter to be wary. A girl’s heart is pure, and ready to love in the twelfth year; if she settles her faith upon you, she may remain constant to the end of her days. But this passion, this inner flame, will serve her ill. To an illegitimate wench, your royal smiles can only bring tears. She will never wear your coronet.”

The prince turned toward me, anxious. “At night, she displays the signs of the frenzy. She moans, slaps her hands, bangs her head, grinds her teeth. In the daytime, she will not speak of this, but laughs and sings, until she ends by weeping.”

The Earl of Gloucester pounded his fist in his lap. “It is not for you to bear witness to her insanity!”

Amabel piped up, quite satisfied to take my family to task. “Denise must snip three boughs of juniper, dousing each one three times in wine, whilst making the sign of the Trinity. If she sets the branches upon her daughter’s pillow, while she sleeps, Marie will be freed from her torments. Of course, you could do these things, if you are in the girl’s presence after compline.” The bitch’s cheeks reddened at the boldness of her implication.

Certainly Henry has my carnal weakness, his father’s and his grandfather’s. But I believe him innocent of the act of intercourse.

The Plantagenet frowned. “I am full of her troubles and choose to watch over her. When she rages, I know best how to soothe her. What you propose, Lady Aunt, is superstitious nonsense, if not heretical.”

Now Amabel whitened, remembering that my heir is the king to come.

Robert scowled, discomfited. “Boy, you are not a physician. Your pity prolongs her madness.”

FitzCount nodded. “Marie must be bound up and left in a dark place.”

My son’s voice deepened. “Mother, may I not marry her, when I ascend to my rightful throne? Shan’t I do what I like, then?”

The conversation had run away from me, but now it flowed back. “The girl is your half-sister; you two cannot wed. But you have my leave to adore her, for it never serves to advise against love. Someday, when you are of age, you will outgrow her attractions.”

The Plantagenet’s teeth flashed white. “Every beauty is alive in Marie. Among all the other maidens, she has no peer. I will never know peace in the arms of another.”

I laughed low, to hear Stephen’s son vow to be true to one woman. “Dear child, pride of my loins! Your veins run with milk and honey.”

Henry cared nothing for a mother’s devotion. “Whatever admiration is paid to Marie is her due, for without question she is the finest, most amiable damsel in all the world.”

Both Brian and Robert’s expressions were glum. I pressed my own lips into a thin line. Groaning sorrow is the usual result of unbridled esteem.

†

Our lords dart off from Bristol, once more to engage our adversaries. In their absence, we ladies rely on the minstrels’ battle chronicles. I permit the castle garrison to cede entry to any and all troubadours who request shelter, in exchange for their news, gossip and verse.

Several sing of the Count of Boulogne’s vile rampage through the southwestern countryside. To lessen the sting of my celebrated escape from his siege, my cousin attempts to retake Wareham. Finding it too strongly defended, his ire grows. Full of bestial fury, he pillages all the territories surrounding Oxford and even ravages further afield, meting out fire and the sword.

At Wilton, the pretender’s forces swarm the nunnery of Saint Etheldreda the Virgin, transforming it into a fortified post, and forcing the good sisters to wait upon them at table, and in bed. The jongleurs insinuate that the lovely abbess is the usurper’s willing concubine. Amabel shakes her head at Stephen’s depravity.

†

The Earl of Gloucester launched three divisions against the convent, and routed the usurper from Wilton. Robert’s regiments looted the town, tossing firebrands onto every roof, dislodging the burghers from their hidey-holes. Our battalions stormed every church, granting no right of sanctuary. Finally, they burst into the nunnery of Saint Etheldreda, smashing the doors down, raping and terrorizing the same women who had been taken against their will once before, and whose voices were too hoarse to scream a second time. The troubadours recount, without equivocation, that the Earl of Gloucester violated the abbess, mingling his tears with her own. This Amabel does not credit, spitting at the scoundrels who repeat it.

†

One particular jongleur, Bernard de Ventadour, skulks about me, ever ready to tell me what I do not wish to know. This afternoon he had the apish temerity to scratch his long nails against my oaken door, and creep into my solar, brushing past a confounded Gerta. When I nodded my permission, he smiled, flaunting his blackened incisors. “Ah, Lady, you are charity itself. Do be soft-hearted and mild, and send for some victuals.”

I dismissed my maid on the errand, curious in spite of my misgivings.

Bernard is tall, but far too thin, and his sonorous voice booms out from a sunken chest. He has agreeable, symmetrical features, limp hair the color of an icicle, roguish brown eyes, and a dank odor. He is affable enough, when he remembers his place, but most often oversteps himself, to my continual irritation.

With great impertinence, Bernard scrutinized my belongings. “The king has spoken of your charms, but not of your gentleness.”

I burned to hear that my once beloved bandied my name among his retainers. “How is it that traitors and commoners discuss their queen so freely?”

“His Majesty shares many of his private thoughts, when he is in his cups. I often sup with him, and his consort, to entertain and distract them from this ugly war.”

Now I was alive with interest. “Surely the Count of Boulogne does not compliment my person in front of Maud?”

The troubadour demurred. “Indeed he does so. Her Majesty is sorely tried by his wandering eye. Lately, she sheds many tears over a lock of red hair that she found in the snow outside the royal pavilion, on the morning after your astounding departure from Oxford.”

I rejoiced that my hated rival guessed at her husband’s link to me. But I would not reveal my satisfaction to a minstrel. “Whosoever discarded it must have intended to mark her renunciation of him.”

Bernard guffawed. “Yes, yes, but Maud is a woman, and a woman does not often see the distinction between an affair that is over and one that is not. Long ago, she granted her heart unconditionally to the king, thinking that he would always be hers to command.”

For the moment, I forgot that the fool was a mendicant versemaker, loyal only to his belly and his purse. “Have you ever known such a bond that did not wither away?”

The minstrel did not flinch from telling me the countess’s secrets. “The queen believes that His Majesty will not break faith with her again.”

I smiled bitterly. “In lust, he has wronged that witch and in lust he will wound her again and again, no matter how they try to hide this from one

another. Their match was an inopportune one.”

Bernard would not agree. “Maud considers the wife of a handsome and virile sovereign to be entitled to share a great romance with him.”

“The larcenous whore deals in stolen position and stolen emotion.”

“Their embrace is an honest one. They couple as true lovers.”

I let out an indiscreet bark, then stood up, remembering my place and his, and casting a shadow over him. I pointed to my door, and the oily, insubordinate man scuttled away without his supper.

†

Spring

My brother’s talent for war waxes full. Gloucester successfully invests the magnificent Castle of Devizes. Without complaint, the archbishop of Canterbury allows the superb structure to fall into our hands. We do not have Bishop Henry’s Wolvesey, but Devizes is an even more splendid palace. Its taking is a credit to Robert’s prowess.

Indeed, the earl wins a whole series of strongholds in the southwest. In victory, he shores up the defense works of each captured keep, requisitioning laborers from its surrounding countryside. Those who will not agree to work for us are made to do so, under duress. The jongleurs relay the growing resentment against my brother’s impressment of manual workers. But I will not allow the songs of minstrels to curdle my high pleasure at Gloucester’s achievements. As of now, we have smashed an open north-south line, from Gloucester to Bristol, to Devizes, to Wilton, to Wareham Castle on the Channel. This path shall stay clear, until the prince shall be old enough to travel it in triumph.

†

Much to Amabel’s pleasure, Gloucester returns to Bristol; she rarely leaves his side.

Oddly, he seems despondent, despite our gains. I presume that his malaise dates from his abuse of a holy sister. His eyes are shrouded, his conversation cheerless. Gerta presses my brother’s pages for information and discovers that the earl is seldom able to sleep through the night.

Gloucester and I come into conflict over his methods of reinforcing our new strongholds, and I have been forced to debate with him in his wife’s presence. I wish the peasants to toil for me, and for the Plantagenet, in duty and in devotion. But my brother reminds me that our revenues are sorely depleted, after our recent offensives. As we lack the funds to launch any new sorties, our defenses must be reinforced with the free labor of unwilling serfs.

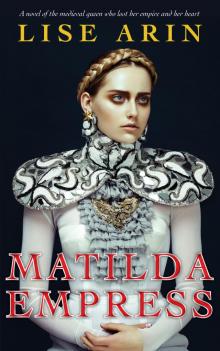

Matilda Empress

Matilda Empress